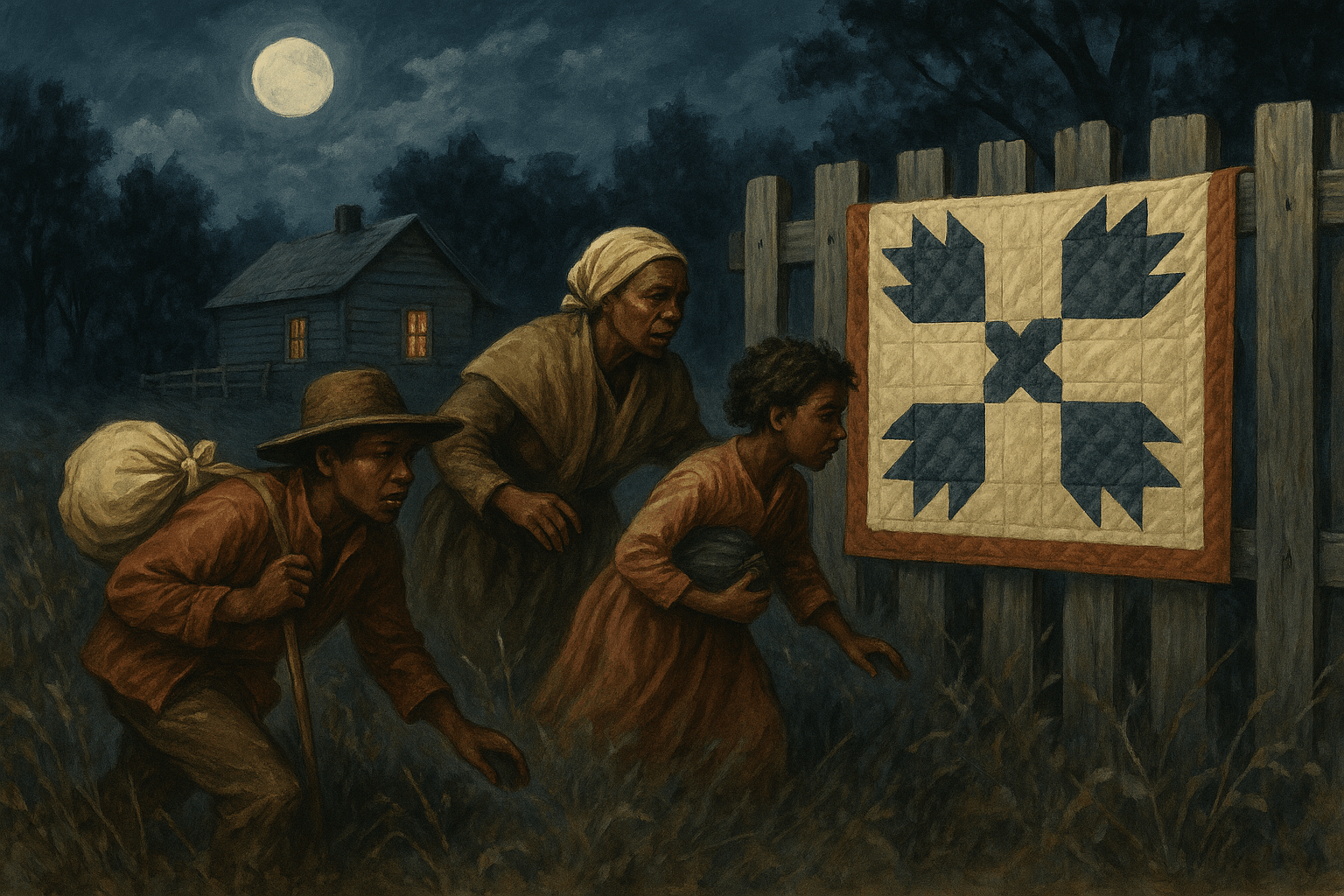

Quilts and the Underground Railroad stand at a pivotal intersection of craft, culture, and freedom. Many people have heard that specific quilt blocks carried secret messages that guided freedom seekers on their northward journey. The idea is compelling because it centers creativity and community in a story of resistance. It is also contested. What follows brings together what scholars can verify, what remains in the realm of legend, and the many real ways quilts and quilters intersected with antislavery work.

The Popular “Quilt Code” Story

The most influential version of the code story was popularized in 1999 by Jacqueline Tobin and Raymond Dobard in Hidden in Plain View, based on an oral account from Ozella McDaniel Williams. They described a sequence of quilt patterns, such as Monkey Wrench, Bear Paw, Flying Geese, and North Star, each carrying instructions for escape. The story quickly spread through news coverage and classroom projects, and it continues to inspire many quilters today. While the book gave a powerful voice to African American storytelling traditions and inspired many quilters and educators, historians have questioned its claims because there is no contemporary documentary evidence to confirm the existence of a systematic quilt code. As a result, the book is often discussed today as a blend of folklore and cultural memory rather than verifiable history, but it remains an influential text in the dialogue about quilts, symbolism, and the African American experience.

What Historians Can and Cannot Confirm

Quilt scholars and public historians have looked for letters, diaries, newspaper notices, Works Progress Administration interviews, or period manuals that confirm a quilt code. To date, no contemporary sources verify a coordinated system of coded quilts. The National Park Service and the International Quilt Museum note that while the code story is meaningful to many, it lacks corroborating evidence beyond one family’s oral tradition. They also point out that other forms of signaling and communication are well-documented, including songs, lanterns, and person-to-person networks.

Many patterns often linked to the code present timeline challenges. For example, Log Cabin designs and names flourish during and after the Civil War, with written references dating back to the early 1860s, which complicates claims that they were widely used as signals in earlier decades. Drunkard’s Path is often associated with later temperance activism, rather than the era when most Underground Railroad activity was at its peak. These dating issues do not preclude creative uses of textiles, but they highlight the disparity between legend and the surviving historical record.

Patterns People Ask About and What We Know

Quilters often ask whether specific blocks have fixed meanings. Some modern explainers assign instructions to patterns such as Bear Paw or Flying Geese. Scholars caution that these attributions are not supported by period documentation and that many named blocks were standardized or popularized later. In short, we can describe contemporary beliefs about pattern meanings, but we cannot confirm them as an antebellum communication system.

Documented Ways Quilts Supported Antislavery Work

There is strong evidence that quilts and needlework played a significant role in fueling the abolition movement through fundraising, messaging, and community organizing. Women’s antislavery societies in the 1830s and 1840s held fairs where quilts and other handmade goods raised money for publications, speakers, and direct aid to freedom seekers. Surviving examples include a star crib quilt linked to abolitionist poet Elizabeth Margaret Chandler and quilts bearing anti slavery imagery used at fairs. These objects served as a means of advocacy, charity, and political expression long before women had the right to vote.

Quilts also appear in Underground Railroad stories in practical ways. Accounts note quilts used to hide people, to keep them warm, and to furnish safe houses run by families who risked fines and violence under the Fugitive Slave Act. These roles are humbler than a universal code, but they are part of the lived texture of resistance.

African-American Story Quilts and Memory

African American quilters have long used textiles to narrate history, faith, and family. Harriet Powers, born into slavery in Georgia, created two renowned narrative quilts that survive to this day. Her Bible Quilt at the Smithsonian and her Pictorial Quilt at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, use appliqué and embroidery to tell layered stories. Powers’s work is not evidence of a quilt code, but it is a powerful record of storytelling through cloth and a reminder that quilts can hold history and meaning far beyond their use as bedcovers.

Teaching and Interpreting with Care

If you teach or curate a program on this topic, you can strike a balance between inspiration and accuracy. Start with what is verified. Introduce the Underground Railroad through people, places, and documented networks. The National Park Service’s Network to Freedom lists hundreds of verified sites, programs, and archives that anchor local research. From there, present the quilt code as a debated legend. Share why it resonates and why scholars remain cautious, using clear sources so readers can weigh the evidence themselves.

Invite discussion of music and language. Spirituals and signal songs have stronger documentation as coded communication, and they open meaningful conversations about culture, creativity, and survival. Pair those sources with quilts made for antislavery fairs to show how textiles and performance together supported the cause.

Encourage making with context. Many quilters design modern pieces inspired by the code story as a form of commemoration. Frame such projects as contemporary tributes rather than as reproductions of a proven system, and consider adding labels that explain the difference between legend and evidence.

A Balanced Takeaway

Quilts were part of the story of freedom, but not in the way popular culture often describes. The best current evidence suggests that quilts raise funds, convey antislavery messages at public fairs, provide warmth and shelter to people, and serve as canvases for narrative art. The idea of a single, standardized code has not been verified in primary sources. A careful reading allows for both inspiration and integrity, honoring the people who sought freedom and those who aided them, while remaining true to the record we can see and study.

Sources and Further Reading

- Smithsonian Folklife Center. “Underground Railroad Quilt Codes: What We Know, What We Believe, and What Inspires Us.” A clear overview of the code story, its appeal, and the evidence debate.

- National Park Service. “The Underground Railroad and the Use of Quilts as Signposts.” Summary of the scholarly consensus and why evidence is lacking.

- International Quilt Museum, “Underground Railroad Quilts?” and “Abolition.” Research pages on the myth, including documented signals such as songs and lanterns, as well as abolitionist fundraising quilts.

- Barbara Brackman. Quilt historian, on the dating of Log Cabin and other patterns. Helpful in understanding why certain blocks are unlikely to have functioned as antebellum signals.

- Spencer Museum of Art. Note on Drunkard’s Path and its association with temperance themes later in the century.

- History.com. “Secret Codes Used to Communicate in the Underground Railroad” provides documented examples of coded songs and language.